The museum has been continuing to meet to discuss specific chapters from the toolkit, after taking a break for a month for the summer. The most recent sessions have covered inclusive leadership and interpretation. Lighter attendance has allowed for more in-depth conversations, one-on-one discussions, and increased openness when talking collectively as a group. These sessions have also marked a shift away from general ideas about inclusion towards specific roles and work within museums. As such, the concepts feel more tangible, and they may help to fill the gap some (including myself!) felt previously when covering broader ideas.

The discussion about leadership overlapped nicely with course content from my SJSU Information Professions class, wherein we explored the differences and similarities between managers and leaders. Being a manager does not automatically make you a leader, nor do you have to be a manager in order to be a leader. There are certain traits necessary for true leadership, which may be innate or learned, and these are crucial in the context of inclusive workplaces. Some of the characteristics included in the toolkit include “being able to adapt, being authentic, having emotional intelligence, and developing good relationships with followers” (Taylor, 2017, p. 74).

Our first activity during the session revolved around these and other traits that make good and inclusive leaders: empathy, self-awareness, humility, good communication skills, among others. We were tasked with picking one of these characteristics and discussing with one of our peers our choice. It was challenging deciding which was most important to me, but I settled on self-awareness. Given my professional experience with a range of different supervisors and management figures, I have learned how important it is for those in leadership roles to see and understand their place, and how their actions (or inaction) have impact. We had a good conversation, which underscored how many of these characteristics overlap, and how it is important for leaders to embrace and foster as many of these traits as possible. While some individuals may have innate abilities, for many it will require ongoing development, work, and self-assessment.

The MASS Action toolkit provides a helpful definition of what inclusive leadership is, in the form of a quote from Lize Booysen: “inclusive leadership extends our thinking beyond assimilation strategies or organizational demography to empowerment and participation of all, by removing obstacles that cause exclusion or marginalization” (Taylor, 2017, p. 74). Our facilitators focused the rest of our session on authenticity as being central to inclusive leadership, and the characteristics of authentic leaders:

- They understand their purpose

- They have strong values about the right thing to do

- They establish trusting relationship with others

- They demonstrate self-discipline and act on their values

- They are passionate about their personal mission (Taylor, 2017, p. 75)

Given the fact that many of those attending these sessions are not in management positions, and might not thus be deemed traditional leaders, we were tasked with considering what our values are and how that might inform us taking on less traditional leadership roles. Our prompt was to consider why we show up to work, on a fundamental level, and what motivates us to do our work.

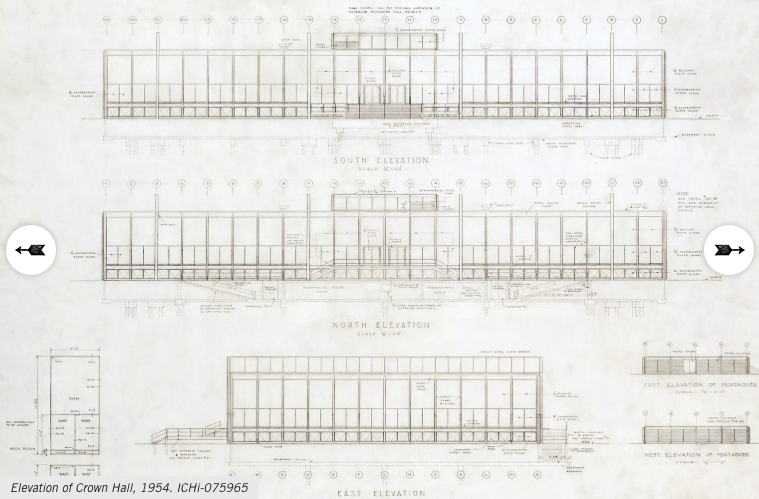

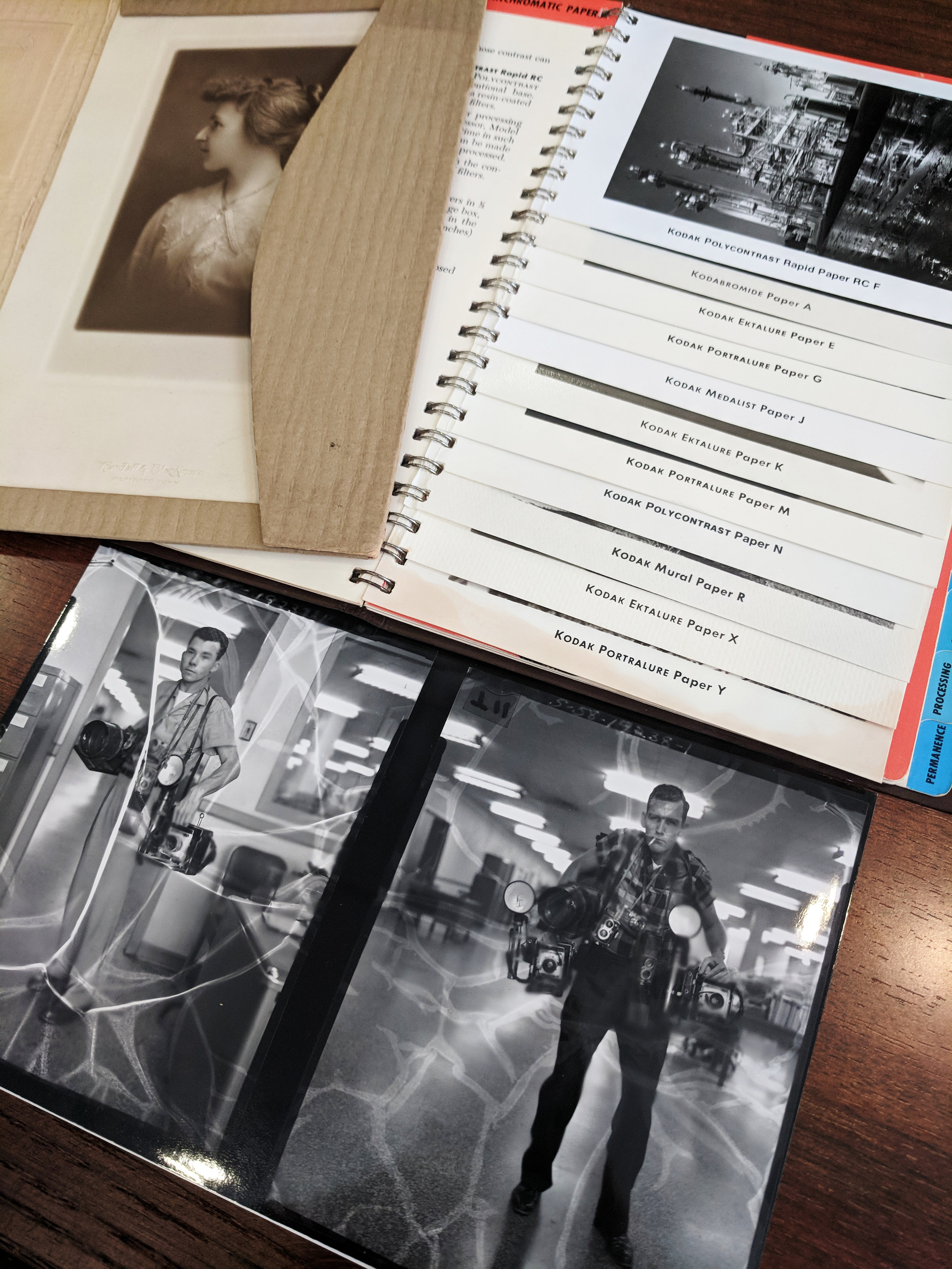

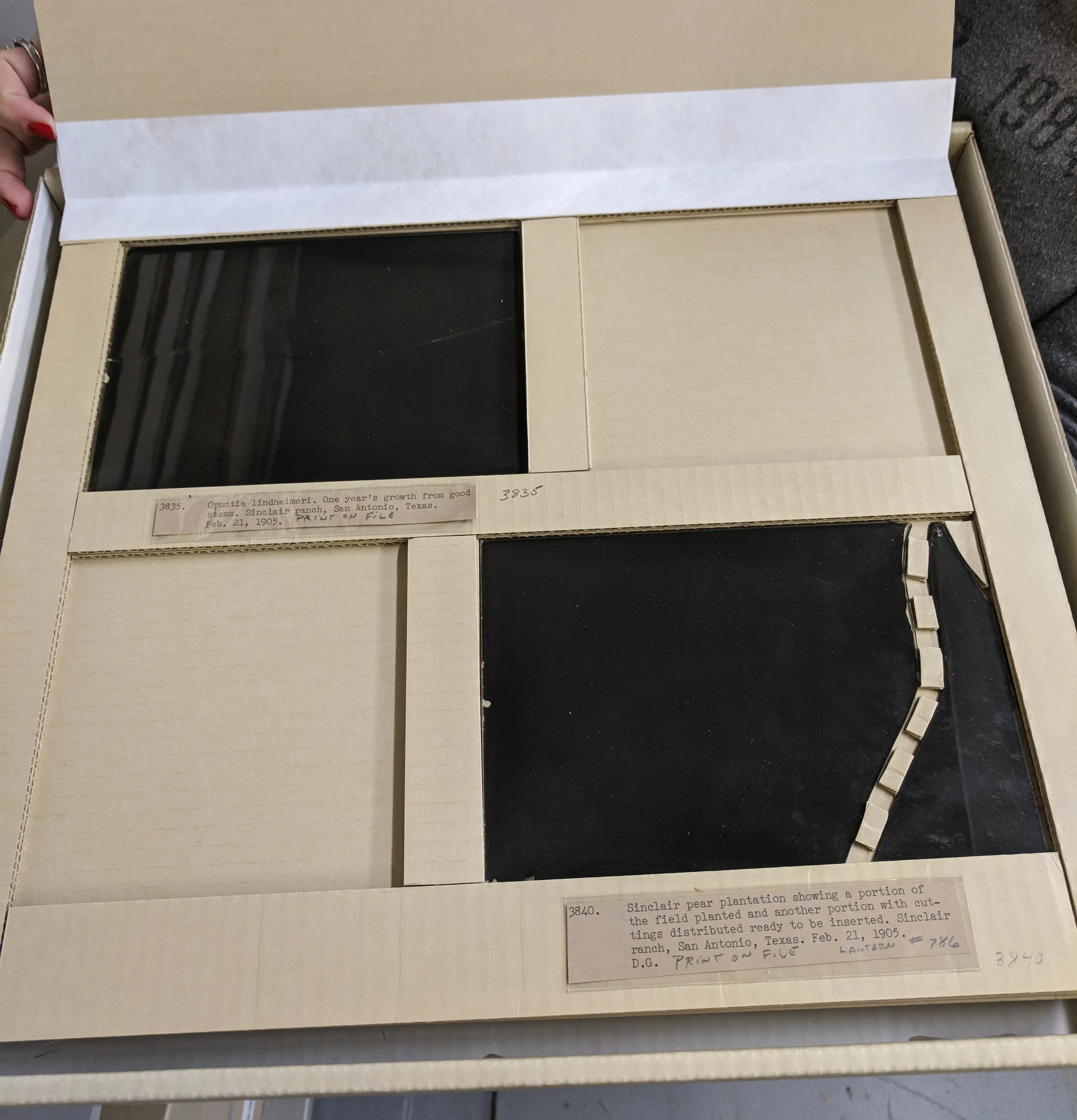

I am no stranger to these questions, as I talk fairly often with peers at other institutions, friends, and family about what drives me to work in archives, libraries, and museums. At the core of it, education and discovery are key for me, and my experiences have been to this end: in digitizing primary source materials, creating metadata, working as part of a team on collection portals and asset management systems, and most recently tackling the physical and intellectual control issues with an inconsistently managed archival collection. My jobs within imaging and photography departments have played a role in providing access to the collections and activities that occur within LAM institutions. I believe folks everywhere should be able to find, access, and learn from the work our museum does, and I hope that my contributions help break down barriers (geographic, financial, physical, cultural, etc.).

It was interesting to hear from staff working in a variety of positions - from conservation to major gifts to curatorial to learning and public engagement. We all have different guiding principles and senses of self-purpose, but this institution brings us together. If we can be conscious of and tap into these values, it seems much more likely that our principles can help guide everyday decisions that will make the museum more inclusive.

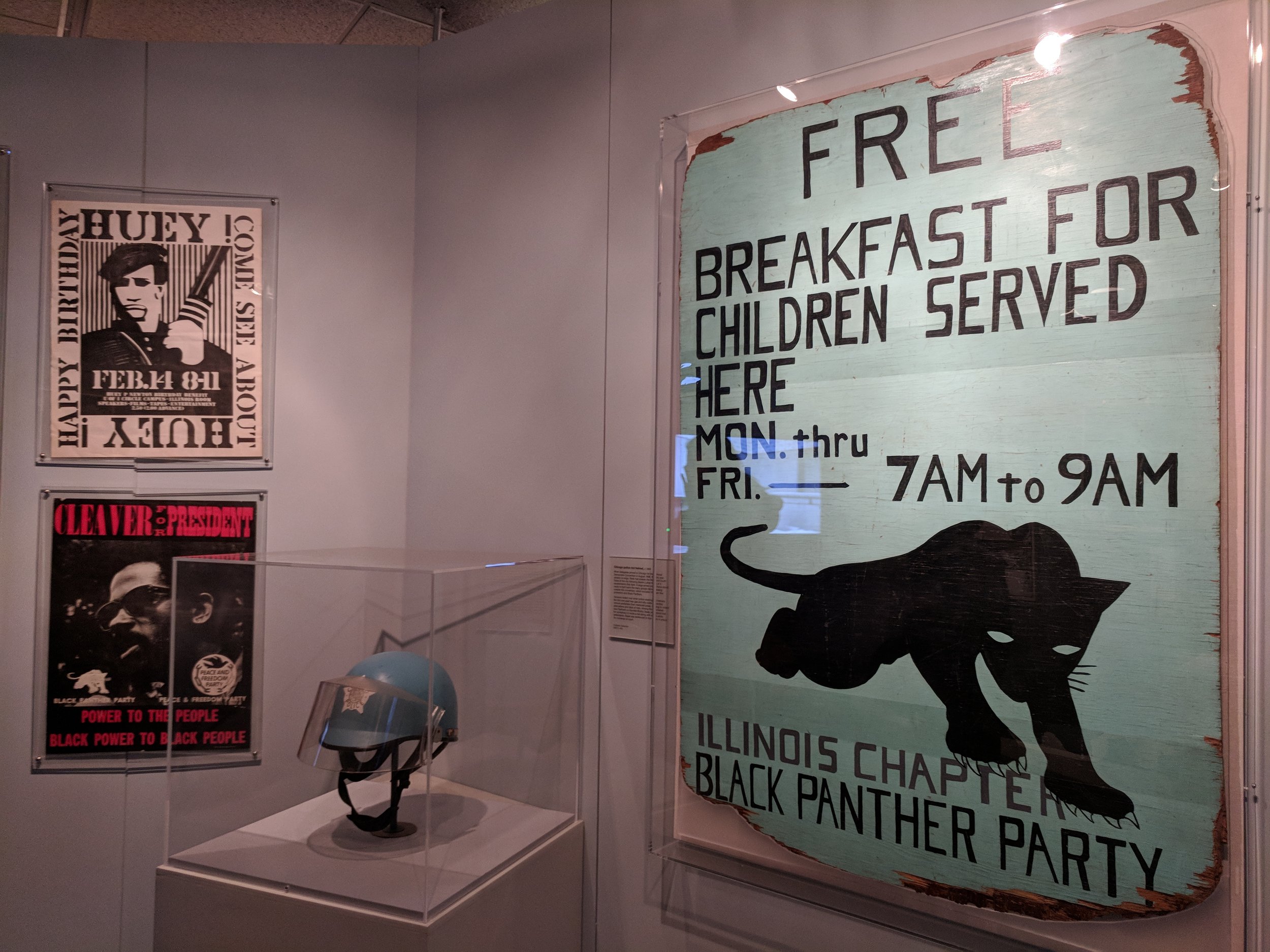

The session on interpretation addressed how the museum connects and engages with audiences through our collections. Interpretation was helpfully defined in the toolkit as “a narrative and a method of communicating to and with visitors… [which] conveys an institutional voice” (Anderson, Rogers, Potter, Cook, Gardner, Murawski, Anila, Machida, 2017, p. 89). Given the tradition of didactic methods in museums, the Eurocentric-dominant perspectives of these institutions have been disseminated as the official cannon. Varying points of view have either been absent or silenced as a result. The toolkit dives into the challenges historic homes in particular face when more fully and inclusively covering the story of a place: “who built this home… were they free or enslaved… at whose expense did the home’s owner make their money” (Anderson et. al., 2017, p. 89)? We may be focused on art, but we still face some of these same questions and many others in regards to interpreting our collections.

Our first exercise during the session helped to highlight some of the ways in which our differing backgrounds inform the way in which we might individually interpret collections. We were each given a reproduction of a work of art from the museum, and we were asked to describe it our partner in under a minute. We then both looked at the image and discussed what was missing from, what was assumed about, and what was highlighted from the verbal description. We shared as a group the challenges of creating the narrative, especially around issues of identity - be it race, ethnicity, religion, gender, or culture.

We then shifted gears to work in larger groups, and we were tasked with thinking about one of two sets of questions: those that pertained to how we interpret our work internally and what stories we tell institutionally; and those that pertain to multivocal visitor experiences with art. I decided to work with a team on the latter idea, and we discussed ideas about collaborations and a more plural experience behind our collections.

Staff shared examples of engaging programs and exhibitions other cultural centers and museums have undertaken, including the Chicago Cultural Center’s Wired Fridays weekly house music dance party, and the Museo Casa de la Memoria in Medellin Colombia. Chicago Cultural Center’s program pulls from and embraces one of the important, yet often neglected, music scenes to emerge from the city. With it, the Cultural Center has provided opportunities to expose more in the community to this style, and to draw in community from different parts of the city. The Museo Casa de la Memoria dedicates a substantial portion of its exhibition spaces to the recorded stories of those who have experienced armed conflict. The museum functions as a space of organization rather than authority, and it embraces polyvocal interpretation through interviews and oral histories. As the toolkit discusses, this type of interpretation honors the lived experience and respects that expertise.

These projects are good models of collaborative and engaging work institutions can embrace. I could see our museum doing even more to this end - collaborating with local street artists to create a series of programs and tours, for example. As previously mentioned, the museum could do more to also address what is absent from our interpretation. The toolkit asserts that aside from or in addition to interpreting “presences” - actual physical, material things - we might “instead emphasize - or be self-consciously aware of - the ‘absences’ - the stories and artifacts of those whom traditional history has largely forgotten or those whom dominant cultural thinking (infused as it is with racism, sexism, classism, anti-Semitism, homophobia, etc.) has deemed unworthy” (Anderson et. al., 2017, p. 93). Making more conscious efforts in setting concrete quantitative goals to exhibit groups underrepresented at our museum may be a start. Interpreting artworks in the larger context of museum studies, including problematic and troubling provenance may be another.

At the end of this chapter in the toolkit, the authors provide a list of strategies for transforming interpretation, which includes:

- Expanding research

- Learning critical race theory

- Finding who is missing

- Exploring intersectionality

- Creating polyvocality

- Listening and making space

- Recontextualizing

- Asserting a position

- Conducting culturally responsive evaluation

- Mining the human

- Embracing collaboration during interpretive planning from:

- Expert advisors

- Focus groups

- Community conversations

- Co-creation

- Reconsidering and reimagining in-gallery interpretation through:

- Design spaces

- Labels

- Audio and multimedia tours

- Response stations

- Social media (Anderson et. al., 2017, p. 99-101)

There is much our museum can and should do to be more inclusive in its interpretation. I feel that a good place to start would be embracing the notion that museums are not and cannot be neutral, and that we need to assert a position when it comes to important issues. The institution can make it clear that it is a welcoming, safe space in asserting its values, and reflecting those values in how it interprets its collections, designs exhibitions, and develops programs.

Anderson, A., Rogers, A., Potter, E., Cook, E., Gardner, K., Murawski, M., Anila, S., Machida, A. (2017) Interpretation: Liberating the narrative. MASS Action Toolkit. Retrieved from https://static1.squarespace.com/static/58fa685dff7c50f78be5f2b2/t/59dcdd27e5dd5b5a1b51d9d8/1507646780650/TOOLKIT_10_2017.pdf

Taylor, C. (2017). Inclusive leadership: Avoiding a legacy of leadership. MASS Action Toolkit. Retrieved from https://static1.squarespace.com/static/58fa685dff7c50f78be5f2b2/t/59dcdd27e5dd5b5a1b51d9d8/1507646780650/TOOLKIT_10_2017.pdf