Last month, I traveled to Washington D.C. for the IS&T Archiving conference. I headed out a few days early in order to meet with a couple of archivists at the Smithsonian. My first stop was the Smithsonian Institutional Archives, and my second stop was the National Anthropological Archives.

I met with the photography archivist, Marguerite Roby, at the Institutional Archives, and it was incredibly helpful meeting with someone managing collections so similar to those I’m overseeing at the Art Institute of Chicago. We discussed issues we’re currently facing, and she provided suggestions based on similar challenges she’s encountered. She stressed finding an approach and sticking to it, for consistency it’s not about the perfect solution, rather one that will work in most situations and will produce repeatable results. She also encouraged our department to work collaboratively with other departments to learn more about our materials, and to foster institutional ownership of the collections.

She also provided the history of the Institutional Archives, whose complicated past mirrors our story. With institutional archives, especially photographic material, it seems as though the distinction between “working” and “archival” material is often hard to make. At AIC, this is reflected in the fact that the Imaging department, that which is currently making new documentation for the museum, is still tasked with managing all historical photographic documentation. At Smithsonian, progress has been made in the form of one centralized repository for all institutional documentation, but there is much work to be done to sort and catalog a legacy of inconsistent management. It was eye-opening hearing her thoughts about the unique challenges embedded within photographic institutional archives, which I’ve felt intuitively, but have never been able to pinpoint exactly.

Additionally, we talked shop about image records, metadata, information management systems and workflow, storage, and digitization. While Marguerite is dealing with a scale of material that far surpasses our collections, learning about the ways in which our day-to-day work is similar and differs gave me ideas on what we can improve. It confirmed areas where we’re on the right track, and areas that need more attention. We also toured the on-site storage in the Smithsonian Institutional Archives building in D.C. The majority of photographic material is located elsewhere, but I was grateful for the opportunity to take a look at some of their archival material. One item in particular, the custom slide cabinet and vertical viewing station, caught my eye.

It was wonderful discussing archives, and institutional archives in particular, with a professional with so much experience and knowledge.

Storage in the Institutional Archives office building

Slide storage and viewing cabinet

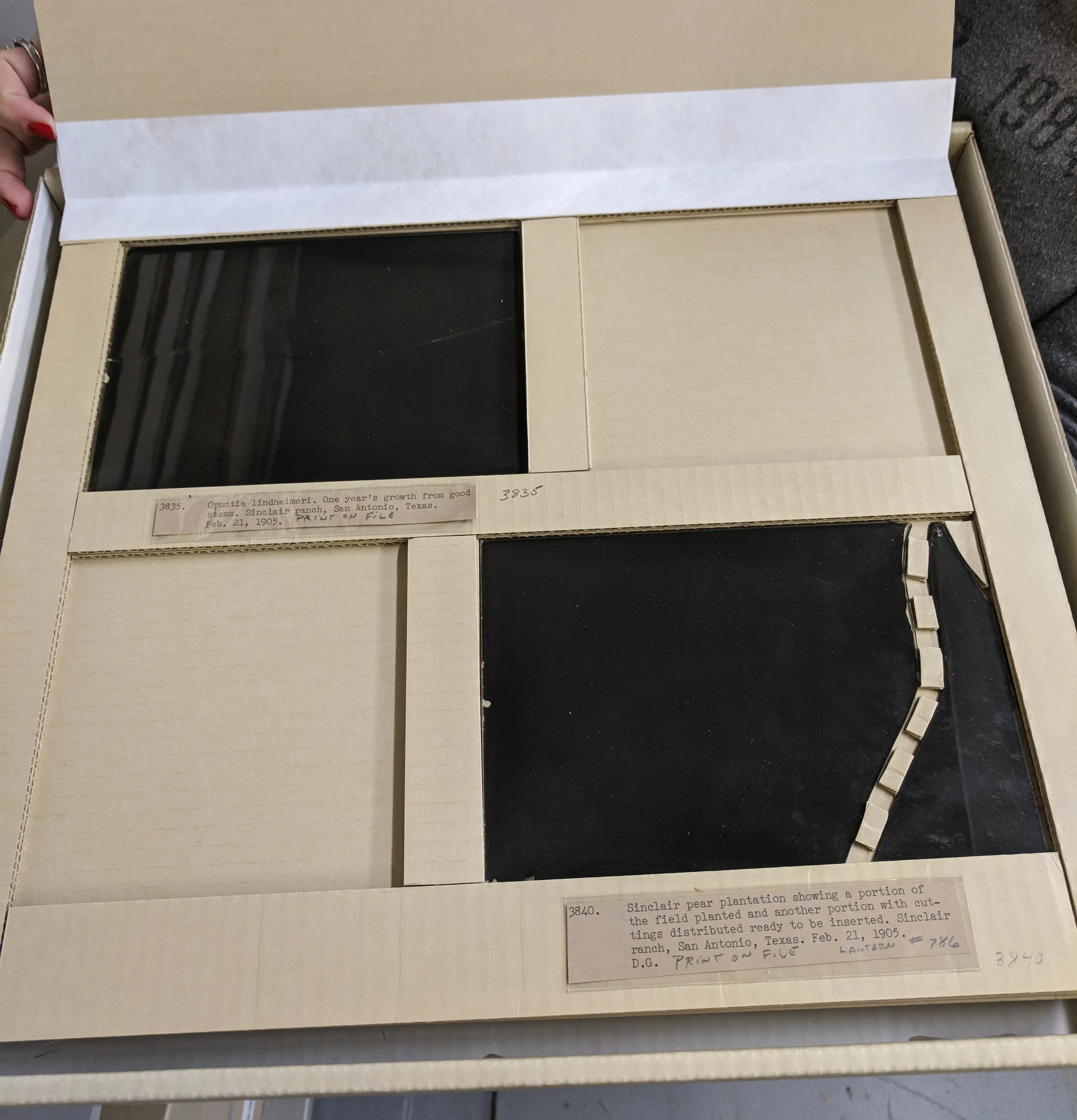

Custom housing for glass plate negatives

Material to-be-sorted from a departing Smithsonian staff member

The next day, I met with photograph archivist Gina Rappaport, who manages the National Anthropological Archives. Her office and storage are located in one of the off-site facilities outside Washington D.C. - one of the warehouse spaces I’ve long wanted to visit.

She told me about the Archives’ long history and how ownership and management as shifted over the decades. Paralleling the Institutional Archives, and our own, it’s interesting to learn how common a reality this is for archives - and it’s a reality which has a huge impact on archivists’ work. Uneven oversight results in piecing together puzzles and backtracking to revise work previously done. This is further complicated with Gina’s material, since there are so many different creators. Institutional archives can be considered mainly in terms of the institution itself as creator and subject, but more traditional collections like the National Anthropological Archives have unique creators and subjects.

We discussed physical and intellectual organization of the archives. She helped answer some of my questions about the utility of creating finding aids for our collection, and how to go about resolving physical reorganization which has resulted in a loss of information about material. These management issues made it clear how important it is to have trained archivists overseeing materials like these. While interpretation of collections is good, it can’t happen without measures in place which allow for the safe storage, retrieval, and care of these materials.

She led me on a tour of some of the photographic archives storage space in the building, as well as some of the general museum collections storage, primarily for the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. The building has been custom designed to maximize storage space, with 435,000 square feet dedicated to the collections. This includes rows upon rows of stationary and compact shelving units filled with historic negatives and prints. The photographic archives are beautifully housed, and Gina discussed their good fortune of having volunteers dedicated to making custom housing for unique or unstable materials. This includes floating mylar supports so researchers can look at original negatives without having to touch them. They also have extensive cold and frozen storage both on- and off-site, and a comprehensive digitization program.

These more traditional archives gave me a better sense of context about archives on the whole, and the ways in which our institutional archives fit in the larger field.

One small section of photographic archives storage for the National Anthropological Archives

Nitrate negatives, soon to be stored in freezers

Custom housing for glass plate negatives: mylar support to allow viewing and reduce handling

I’m incredibly thankful for the chance to spend so much time talking to these archivists, and for the opportunity to tour their facilities and see their collections. The field of cultural heritage is perpetually overworked and understaffed, so it’s a testament to the generosity of staff like Marguerite and Gina to take time out to meet with me. I learned so much from both of these visits, and I’ve made some valuable professional connections. I hope that I’ll be able to pay it forward in the future, especially once I have more formal archival training under my belt.