I recently met with Julie Wroblewski, the senior archivist at the Chicago History Museum (CHM), to discuss the state of the archives program at the museum and future goals for its development. I worked at CHM several years ago, but sadly our time at the institution did not overlap. A colleague, and former archivist from CHM, introduced Julie and I recently, and my current enrollment in the Archives & Manuscripts course in my MLIS program seemed like a perfect opportunity to reconnect and put into context what I am learning.

Julie is a certified archivist with an MLIS from Dominican University. She also recently completed an MA in Digital Humanities from Loyola University, and received her digital archives specialist certification from the Society of American Archivists. Previous work experience includes the role of Archivist and Special Collections Librarian at Benedectine University, Project Archivist at Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum, and Project Archivist at Lake Forest-Lake Bluff Historical Society. Her experience makes her well qualified for her current position, especially given the changes the collections unit is undergoing.

The museum is a stand-alone institution, and there is both a library and an archives within it. Hierarchically, the 3D museum collections, archival collections, and library are all situated under the collections unit, so the staff work closely with one another. The archives program at CHM is extensive - a fact I did not fully grasp when I worked there. The archival collecting scope aligns with the overall policy for the museum. The areas include: living, working, and governing the metropolitan area (including the broader suburbs around Chicago), the built environment, and individuals and ideas (Chicago History Museum, Collecting scope, 2017). Each of these areas is further broken down into topics, all of which are represented in the archives. Examples of these subjects include neighborhoods, class, leisure, business, labor, electoral politics, citizen action movements, and urban planning (Chicago History Museum, Collecting scope, 2017). Needless to say, there are a broad range of ideas represented in the collections, but they are all generally geographically focused in the Chicagoland area.

Screenshot of an image from one of the museum’s permanent exhibitions

Given the wide range of topics covered in the archives, its user base is wide and varied. Requests are primarily fielded through the research center, though she mentioned she assists with queries which prove to be especially challenging. When I worked at CHM, I would walk through the research center on a daily basis, and I was always amazed by how consistently busy it was, and by the range of individuals visiting and materials they were using. Indeed, they information needs of users include genealogical research, architectural drawing requests from homeowners, primary subject material for Chicago History Fair project for students, and both broad and specific subjects in the archival collections driving the development of new work by authors, filmmakers, and academics. The research center was recently able to eliminate the fee to visit and use the archival and library collections, so now even more of the city can use the institution’s resources. Requests from those outside the city is also welcomed through the use of local freelance researchers.

There are several distinct collections areas managed by archivists at the institution: architectural drawings and records, prints and photographs, and archives and manuscripts. Julie is currently focusing her efforts on the first and last, and the museum is currently seeking a new archivist to manage the prints and photographic materials.

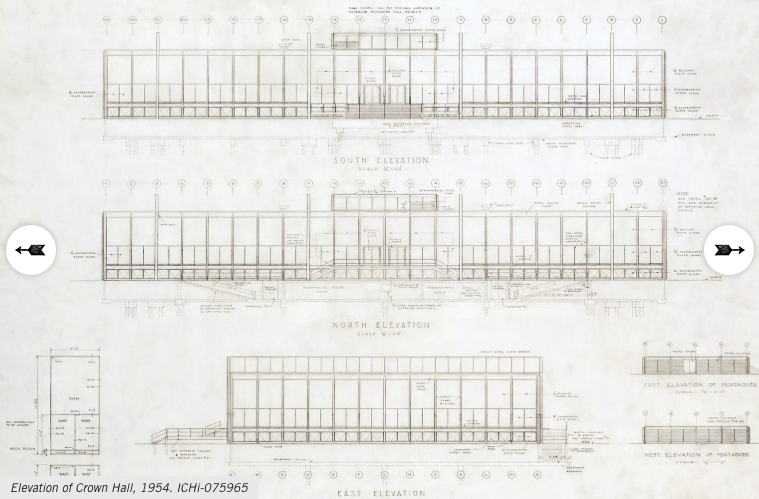

The architectural drawings and records highlights the metropolitan area’s scope and variety of buildings. It includes both famous and lesser-known architects and architectural firms, and collecting efforts have prioritized the acquisition of entire archives of the creators (Chicago History Museum, Architectural drawings and records, 2017). The collection is comprised of architectural drawings, documents, photographs, and some 3D material which is managed separately. The Holabird & Roche/Holabird & Root architectural drawings and records, 1885–1980 and Harry Weese Associates architectural drawings and records, 1952–78 are two prominent collections within architectural drawings and records (Chicago History Museum, Architectural drawings and records, 2017). Much of the material in these collections can be challenging to work with, given the scale and relative fragility of many drawings and blueprints. Julie indicated that a good portion of these materials are stored off-site, and that much work needs to be done to improve the discovery of these holdings.

Screenshot of a sample archival document from the architectural drawings and records collection

The prints and photographs collecting area is that which I am most familiar, as much of the work I did in the photography department at CHM was digitizing negatives and prints for licensing requests. There is an incredible volume of content at “1.5 million images and more than 4 million feet of moving images” (Chicago History Museum, Prints and photographs, 2017). In addition to the sheer number of items, a wide range of media are represented: “prints, including etchings, engravings, and lithographs; photographs, including cabinet cards, cartes de visite, cased images, stereocards, paper prints, and negatives; broadsides; posters; postcards; greeting cards; and moving image film and video” (Chicago History Museum, Prints and photographs, 2017). My favorite collections I had the opportunity to handle and digitize were the Hedrich-Blessing architectural photographs and the morgue from the Chicago Daily News. The majority of these materials are stored at the museum.

Screenshot of a sample photograph from the prints and photographs collection

I am the least familiar with the archives and manuscript collection, so fortunately this is one of the storage areas we toured. There are over 20,000 linear feet of materials, and this is the one collecting area which does include content related to broader American history, especially as it pertains to the country’s early history. Archives and manuscripts include “unpublished materials including correspondence, diaries, business and financial records, meeting minutes and agendas, membership lists, research notes, scrapbooks, scripts, sermons, and speeches” (Chicago History Museum, Archives and manuscripts, 2017). Collections which see a lot of use are the Red Squad files - which have challenging access restrictions - and the Chicago Division of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters records, 1925–69 (Chicago History Museum, Archives and manuscripts, 2017). A large storage space is located in the museum to house some of these materials, but given square footage limitations and the need for more efficient shelving, some collections are stored off-site.

Screenshot of a sample archival manuscript from the archives and manuscript collection

Julie showed me a portion of the storage spaces in the museum, which are not open to the public. We walked past the cool and cold storage - used primarily for still and motion film and color prints. Our next stop was the primary archives and manuscript room. The spaces has several computer stations and large working spaces for processing. Additionally, there is a clearly defined area dedicated to largely unprocessed collections.

Storage space at CHM

More storage

Efficiency and backlogs were a topic that came up repeatedly throughout our conversation. I knew that the museum historically struggled with a substantial backlog, and Julie indicated that the archival collections were not immune to the problem. Fortunately, she has been making substantial progress to reduce unprocessed collections. She employs a variety of strategies to this end, with More Product, Less Process - or MPLP - featuring prominently in the success. Reflecting on previous finding aids, there had historically been a tendency to approach description from a historian’s rather than archivist’s perspective. Rather than focusing on providing a few useful access points, collections were exhaustively described.

Julie also uses processing plans to help go about work strategically. These plans include timelines to provide benchmarks for work, and she uses spreadsheets to document the work she (and volunteers and interns) do while processing collections. She has also taken a note from agile development strategies used by software developers, and she will often organize work into two week chunks. This helps break down complicated and seemingly daunting tasks into more manageable portions, and it helps keep the processing plan on track. Collectively, all these efforts have resulted in the archives backlog shrinking, all while she continues to take in new collections and faces a staffing shortage.

Capacity is an issue, especially given the fact that Julie is the only archivist on staff at the moment. The consequences of this reality are reflected in two ways in regards to growth of the collection: the nature of acquisitions and the material types currently permitted. Currently (and historically) donations have accounted for roughly 80-90% of new acquisitions in the archives. Staffing is the limiting factor in the solicitation of archival collections, especially since it often takes a substantial amount of time and effort to build relationships, and these types of acquisitions can take years before they are completed. Julie mentioned that some exhibitions have helped to kickstart these relationships, especially with communities who were unaware of CHM and who are underrepresented in the collections. Gaps she would like to address include materials created by and that are about the south and west sides of Chicago, as well as communities of color and the Muslim community in the city. Archivists at CHM will likely need to actively solicit materials to more fully round out the archives.

Potential donors can facilitate the process through the online form

Additionally, the museum does not accept born digital content as is outlined in the collecting scope and policy. Julie recognizes that this is problematic, as the majority of archival material being created today is likely digital. As such, there is a chronological gap that has the potential to grow, with material from the 2000s and on simply not being present in the holdings. Limitations in IT, especially as it pertains to infrastructure and the development of a digital preservation plan, are the primary source of this issue. In order to take this on, it will be necessary to have robust staffing and resources to support the substantial amount of work necessary to support born digital material. Julie is actively working on remedying these current limitations, and she hopes that they will begin collecting this type of material in the next few years.

Related to the current technological barriers at CHM, Julie stressed the necessity of emerging archivists to embrace new developments. When I inquired about specific tools or processes, she reflected on the fact that technology changes quickly and that above becoming an expert in one specific application, students should seek to be well-rounded. Competency should be reflected in gaining a range of experiences in order to learn how to use the next new thing, and to develop a foundation and comfort with using technology. She also reassured me that the technical aspects of archival work are not as complicated as they may seem, and that newcomers like me need to approach finding aid encoding and digital preservation with patience and humility.

One especially interesting idea Julie brought up repeatedly, and perhaps many of us do not fully consider when going into this field, is the necessity of relationships. She indicated a variety of ways in which she is actively strengthening ties within the institution - from working with curators to strategize collections building activities to the collaboration with the library and research center to learn what collections are being requested most frequently. Rather than acting as a silo, she understands the need and value in seeking out the experience and knowledge of other staff, and using it to strengthen the archives. This has resulted in the development of a series of brown bag meetings for staff, where Julie presents interesting new acquisitions to raise internal awareness of the collections.

The research center is an important ally for archival activities at CHM, especially because most external research requests are filtered through this department

Externally, she has been forging connections between current events and archival collections through programs and events, which often take place off-site. This helps acquaint communities, neighborhoods, and organizations with CHM and its archives, and it demonstrates the relevancy of the collections. Julie has developed a strong intern program, which is helping to train the next generation of archivists. As she is going about her work on a day-to-day basis, she keeps a list of candidate processing projects for emerging professionals. These real-world projects feature concrete aims, realistic deadlines, and the types of challenges we will face as archivists. Finally, she maintains close ties with other professionals in the field, especially those with similar collecting scopes. They work together to determine where materials might be a best fit, and they can serve users better by understanding where to refer individuals to with specific requests.

References:

Chicago History Museum. (2017). Architectural drawings and records. Retrieved from

https://www.chicagohistory.org/collections/collection-contents/architecture/

Chicago History Museum. (2017). Archives and manuscripts. Retrieved from https://www.chicagohistory.org/collections/collection-contents/archives-and-manuscripts/

Chicago History Museum. (2017). Collecting scope. Retrieved from https://www.chicagohistory.org/collections/collecting-scope/

Chicago History Museum. (2017). Prints and photographs. Retrieved from https://www.chicagohistory.org/collections/collection-contents/prints-and-photographs/