The last scheduled session to meet to discuss MASS Action covered the second half of chapter three of the toolkit, Organizational Culture and Change: Making the Case for Inclusion. The reading covered the various ways in which individuals, teams, and organizations can approach change, and how change is inherently difficult. The intent of the content was to outline different frameworks that can be used to guide the work. I connected with the steps Thomas Cummings and Christopher Worley (2009) developed through their consultancy work:

Motivating change

Creating a vision

Developing political support

Managing the transition

Sustaining momentum

The necessity of a change leader is explicit in each of these steps. Though previous discussions in MASS Action meetings have made it clear staff feel that our current hierarchy is a detriment to the organization, leadership is necessary in order to effect change. This may be a tricky balancing act, but these meetings have demonstrated that is possible for ownership of processes to be shared, and for leaders to facilitate rather than dictate. I have found this to be a heartening aspect of this program, and it encourages me to see the different ways leaders act in this setting. I hope this can be translated out into the broader work of the institution as a whole.

The concept of divergence and convergence were also covered in the reading, especially as it pertained to communication as dialogue. We ended up discussing ideas related to this during the meeting, as participation in MASS Action at our museum is voluntary, and so it has become self-selecting. This is likely beneficial in that it seems there is a level of comfort in discussing challenging ideas, we have hopefully been building trust over the last few months. By the same token, more involvement is needed across the museum in order for change to happen across all levels of the institution.

It has been mentioned on several occasions, and I have also felt, that there is a disconnect between these meetings and the rest of our work within our departments and teams. Whether it is due to apprehension, fatigue/burnout, skepticism, or a lack of time or interest - including notions of “this doesn’t affect me so why should I care?” - there are a lot of staff not coming to the meetings. This is especially the case among white men, who make up a considerable portion of our museum staff, especially in managerial capacities. The challenge I keep thinking about is how we go about bringing more folks into the conversation, and having productive conversations about diversity and inclusion. After all, this will only work if there is buy-in from enough people to bring about and make stick meaningful change. And how do we foster convergence if a broader cross-section of the museum is represented at the meetings, if what is being proposed challenges the status quo?

Another framework presented in the reading was developed by Mark Kaplan and Mason Donovan (2013), and it presents practical phases that I think we could embrace moving forward:

Research

Resource allocation

Implementation and integration

Measurement and recalibration

The first two phases in particular stuck out to me, as our meetings have repeatedly returned to questions of how we can actually go about doing the work to bring change and bring about greater inclusion to the museum. The idea of getting some basic data about staffing, especially as it relates to gender, race, and pay grades, is absolutely necessary - this is research that must be done. We need to know what our weaknesses are and gauge the effect of future changes put into place, so baseline information is key. Additionally, administration needs to understand and commit to providing financial, human, and time resources. This will not be a one-off project, but it will take ongoing work. And when staff are already feeling burdened with work and too few resources, it will be challenging to get wholesale buy-in unless compromises are made elsewhere.

The toolkit also provided suggestions on ways of ensuring inclusion through means of affinity networks, a dedicated diversity and inclusion department separate from human resources, and diversity council and task forces. It is good that the museum is looking to bring on consultants to help guide us, but we also need dedicated teams. This will help ensure the work happens, even after consultants leave, it may help to provide room for more folks at the table, and it will show commitment to change. The logistics of any of these teams, groups, or departments will pose their own challenges, but it is likely that the net gain will be worth it.

During the meeting itself, we were asked to think ahead and consider what we want the museum to be. We were tasked as working in pairs to create a headline 50 years from now that reflected success in the museum’s transformation as it relates to diversity, equity, access and inclusion. My partner and I focused on collections, and equity between solo exhibitions for female and male artists. We also thought about bringing art to the people, rather than relying on them to come to us, since there are many barriers to entry. We dreamed of a sustained partnership where collections are loaned to public schools and libraries throughout the city. It was interesting to hear all the ideas staff came up with, and it was a nice opportunity to hope for a much different future.

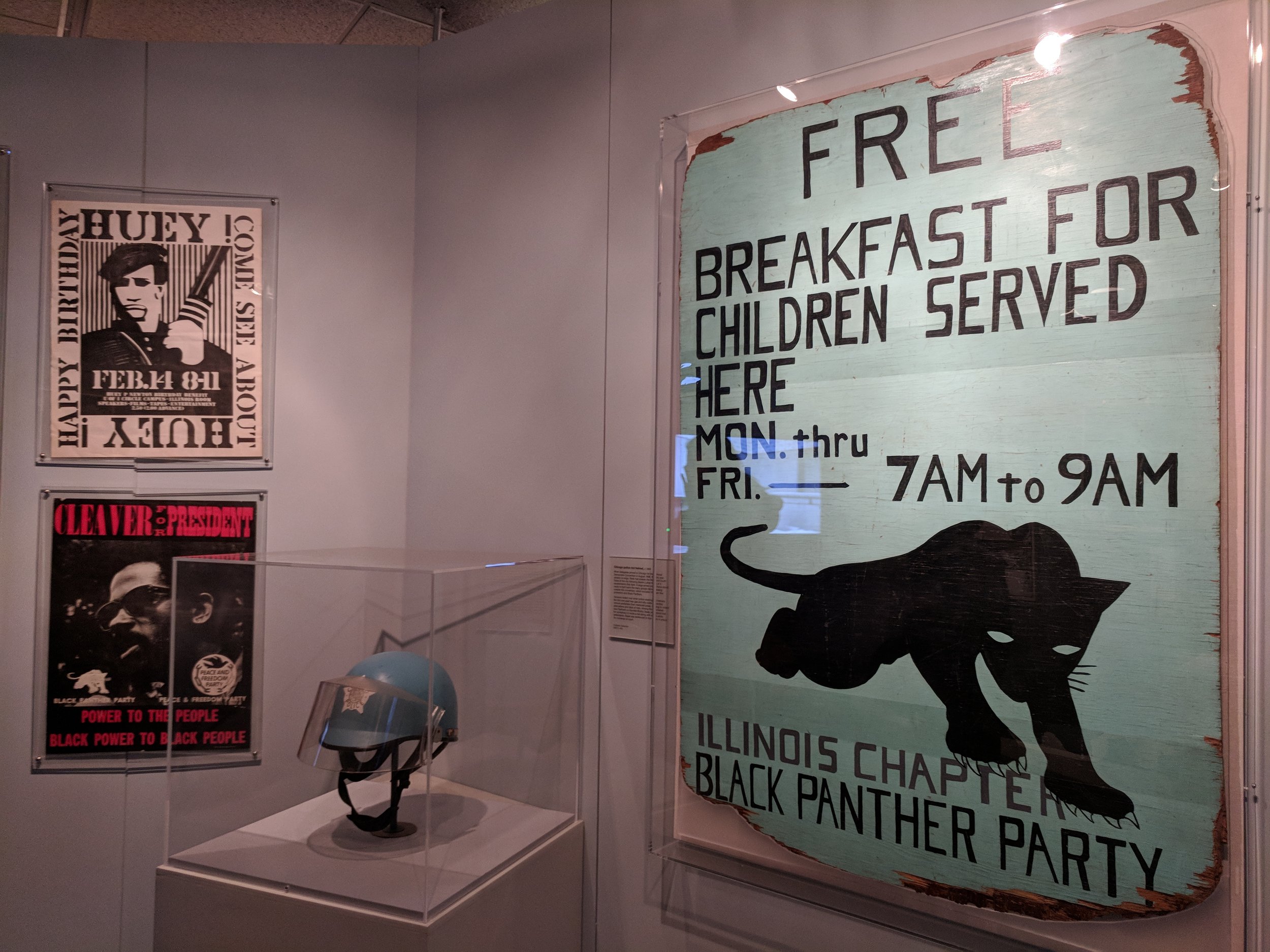

We then broke into groups to discuss ways of actually achieving those headlines, in individual, group, and institution-wide actions. Our group determined that presenting about MASS Action to our departments, especially where attendance has been low, would be worth pursuing. We also discussed how groups might schedule opportunities to meet with staff from other departments to brainstorm ways of bringing about change, in ways relevant to our disparate work. On a larger scale, we discussed how the museum should begin rethinking the ways in which it divides its collections, and in so doing, makes implicit biases and norms known. Curatorial departments seem as though they are always in a state of flux, so it seems reasonable to consider to these divisions might be further altered to minimize making normal white Christian art and “othering” everything else.

The meeting ended in the team leaders compiling all the groups’ action ideas, and reading them to us. There were a wide range of ideas, some immediate with a low barrier point, and some tackling larger systemic issues. I took to heart the idea of setting time on a regular basis to go and connect with collections in the galleries, and experiencing interactions visitors have with each other and the material presented. I rarely break away from work to reflect on what this institution is, and I think it would be grounding and helpful to understand how others perceive our holdings and museum as a whole. Regular time spent in the galleries could also help inform how the museum interprets its collections. One important institutional-level change I would like to see, would be greater input and feedback from the community on interpretation. Having just a few individuals in charge of the selection and presentation of collections contributes to limited narratives about art and history. We need to make room for community curation - both from non-curatorial staff and from the public. I believe this would help considerably in making our museum a more inclusive space for all, and it would help deconstruct the grand narratives which often reign supreme in cultural heritage institutions.

Though there is not yet another meeting scheduled to continue the MASS Action readings, it seems guaranteed that this work will continue. We have yet more to read from the toolkit, and it has become apparent from the meetings that there is a portion of staff who want to see change. Meeting leaders have also been reporting on how they are translating the conversations we are having to administration, and future actions that may be taken as a result of the program and a general need for greater inclusiveness. There is forward momentum, hopefully meaningful change will come as a result.

Cummings, T. G., & Worley, C. G. (2009). Organization development & change. Mason, Ohio: South-Western/Cengage Learning.

Kaplan, M., and Donovan, M. (2013). The inclusion dividend: Why investing in diversity & inclusion pays off. Brookline, MA : Bibliomotion, Inc.