The time-based media symposium Unfolding: Production and Process was hosted by the Art Institute of Chicago this fall. I attended last spring’s two-day presentations, and I have been working with one of the organizers - the museum’s time-based media conservation fellow - on other projects at the museum. Given the interdisciplinary nature of the work, and my coursework relating to digital curation, I was excited for the symposium:

“From the selection of formats during production, to the continual reformatting of moving image works, to ‘reconstructions’ of works that are partially lost or obsolete, choices of assessment and care are interwoven with how artworks are seen and remembered. Artists can be critical stakeholders in conservation approaches, including repositioning their past works into new contexts or modes of display. Further, the transfer between formats as technological platforms change provides opportunities to revisit an artwork’s identity or assess the underlying attributes of an analog or digital format. Unfolding will draw from art history, conservation, artists’ own procedures, and technical fields of expertise with the aim of expanding our collective attention to the in-between moments in the lives of artworks (Art Institute of Chicago, 2019).”

There were four total panel discussions over the course of both days. All of these combined a variety of individual contexts: practicing artists, curators, collection managers and archivists, conservators, and technicians. It was interesting to reflect on the range of perspectives on these complicated works, and how necessary collaboration is.

The first panel in particular resonated with me as it relates to the human aspects of film and video genres within the broader spectrum of time-based media. The moderator posed open-ended questions for us to consider and the panelists to address including: what works are preserved, how we create appropriate and responsible contexts for the work (cataloging, exhibiting, etc), and how we incorporate community into this practice. Speaking to these issues were Liz Johnson Artur, a multidisciplinary artist who works in still and moving images, Abina Manning, from the Video Data Bank, and Jacqueline Stewart, a professor at the University of Chicago and director of the Southside Home Movie Project. All of them spoke to the ways in which their practices intersect with archives, and the interesting dynamics between video and film as documentary and aesthetic. Representation was also an important part of the conversation - from how access is provided in an equitable way, to whether and how materials are made accessible, and what rights creators retain in handing over their materials to a repository. The role of cataloging and description plays a role in this, and so too does the much larger concept of institutionalization of film and video. In the case of the South Side Home Movie Project, Stewart faces the history of conflict as a result of her institution’s role in discriminatory policies in its predominantly black surrounding neighborhoods. Understandably, some of those she works with on potential acquisitions feel a sense of distrust about handing their family’s materials over to this institutional archives. Ultimately, it would seem that relationships are an important part of the process of building, stewarding, and making accessible (or not) this type of time-based media, and that these archives are constantly in flux - not fixed - as a result.

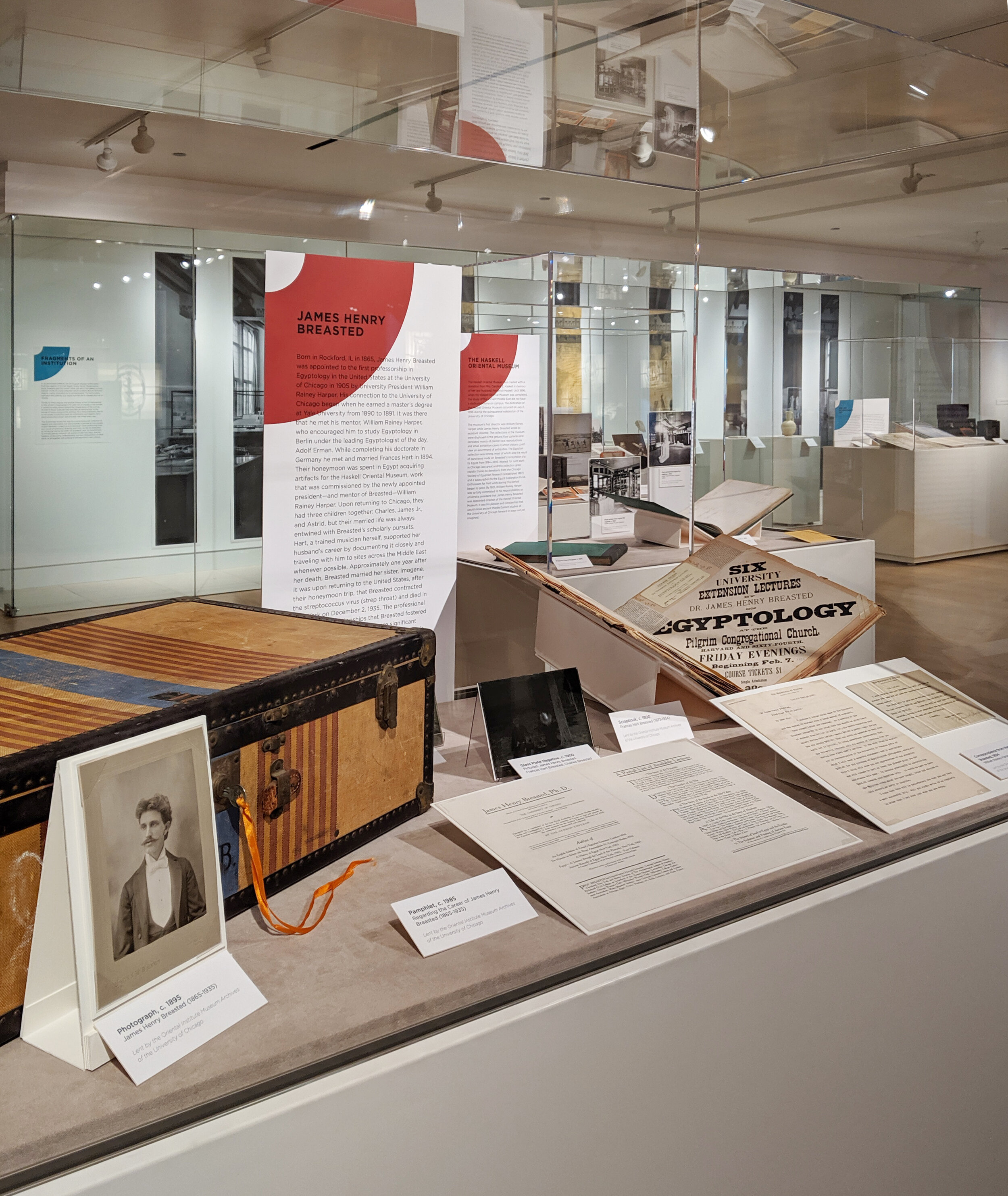

Stewart introducing the South Side Home Movie Project Digital Archive

The last panel on born-digital art also struck a chord, especially given the immediate and tangible examples of challenges within preservation. Jan Tichy, a multimedia artist, discussed a few of his recent conceptual, time-based pieces that were created digitally and are dependent on specific technological tools in order to be accessible and viewable. His work reflecting on the Museum of Contemporary Photography’s collection may evolve over time as their collection grows, necessitating updates and interventions to the original work. His installation on the last remaining and soon-to-be-demolished Cabrini Green building, the resulting documentation of his installation, and the resulting live-streamed footage required different strategies for archiving. Andreas Angelidakis, an “architect who doesn’t build,” talked about his work in both digital and physical environments, and how preservation comes into play with both (Art Institute of Chicago, 2019). He works with online communities like Active Worlds and Second Life, which are both dependent on companies to maintain the underlying digital infrastructure. The platforms disappear when they are no longer profitable. He started making 3D prints of some of his interventions on these platforms, with the idea that these are more stable versions of his digital creations. These physical manifestations have proven to be fragile themselves, though. In another series of work, his work in creating a digital amphitheater through custom software ended up being reproduced in the real world through the creation of soft blocks. These blocks are meant to be rearranged and used in any way people see fit, referencing the interactive nature of the original software. It also means that the blocks are intended to be physically worn down and marked as people interact with them. Mark Hellar, a technology consultant who has worked with museums on conservation projects, talked about some of the specific projects he has helped to troubleshoot. The piece News by Hans Hacke underwent treatment when it was exhibited in 2018. The piece required reverse-engineering in order to make it compatible with contemporary internet technology and RSS feeds. The underlying software had to be completely rewritten due to licensing limitations, reliance on obsolescent platforms, and link rot of the previously used RSS feeds. Fortunately, his studio did permit for changes to be made to the digital system in order to make the time-based media piece function as it originally did. In another case, Susan Kare’s Mac Icons work made its way into MoMA’s collection as both physical sketchbooks and a series of 300 floppy discs. The storage media, the file systems, and the file formats themselves were obsolete, so Hellar helped to create disc images, set up an emulator to view the files, and built a custom server with the emulator so the files would be accessible via a web browser for curators. All of these works, their inherent fragility in their digital (and physical) forms, and the ongoing work required to make them renderable speaks volumes to the challenges of digital preservation of time-based media.

Basic components of a digital preservation plan, as discussed by Small Data Industries’ Fino-Radin

The last portion of the symposium was dedicated to more direct applications of digital curation through a presentation, workshop, and moderated Q&A session. Ben Fino-Radin of Small Data Industries presented on the ‘Past, Present, and Future of Digital Preservation Storage in Museums.’ This company consulted with the Art Institute to provide recommendations on better managing its time-based media collection. This session looked at general trends and best practices in cultural heritage institutions, including considerations like data backup and redundancy, fixity checks, repositories and access, and roles and governance in order to do this work. The workshop allowed participants to learn about some of these practices, namely using digital preservation tools to assess files. Jeff Martin, a consulting media conservator, talked about ways of performing visual quality assurance on born digital video and digitized film works, and Kristin MacConough, a time-based media conservation fellow, introduced specific technology tools to gather metadata about files. Participants had the opportunity to use Terminal to see file directories and create checksums, Exiftool to read information within files (file size, type of encoding), and Mediainfo to generate a variety of additional technical metadata.

I am thankful that there are so many folks in the field who take seriously the challenges of digital preservation, and who are willing to share their knowledge with others. I learned so much during the symposium, and I am excited to learn more through coursework and in real-world applications.

References:

Art Institute of Chicago. (2019). Unfolding: Production and process in time-based media art. [Program].