In the last year or so, I have begun fielding research requests at work. Our archives serve as an important visual repository for and about the museum, as the “corporate memory [which is] preserved so that the parent institution can understand its history” (Pugh, 2008, p. 43). Staff ask for images, and I attempt to locate and make accessible via digital surrogates visual representations of subjects for which they are looking. These are extrinsically motivated, as research, publication, or exhibition projects often drive these requests (Pugh, 2008).

Sometimes requests are straightforward - a known negative which depicts a specific museum collections object. If the negative or transparency can be found within the collection - either via the image number or object accession number - the material is usually easily digitized, and the file and corresponding descriptive metadata from the catalog card and/or negative sleeve can be shared with the requestor. Often, queries are much more vague and do not have specific images associated with them. Questions are open ended: “what images do you have that depict families visiting the museum in the 1950s” or “do you have any images of the museum gardens with flowers blooming?”

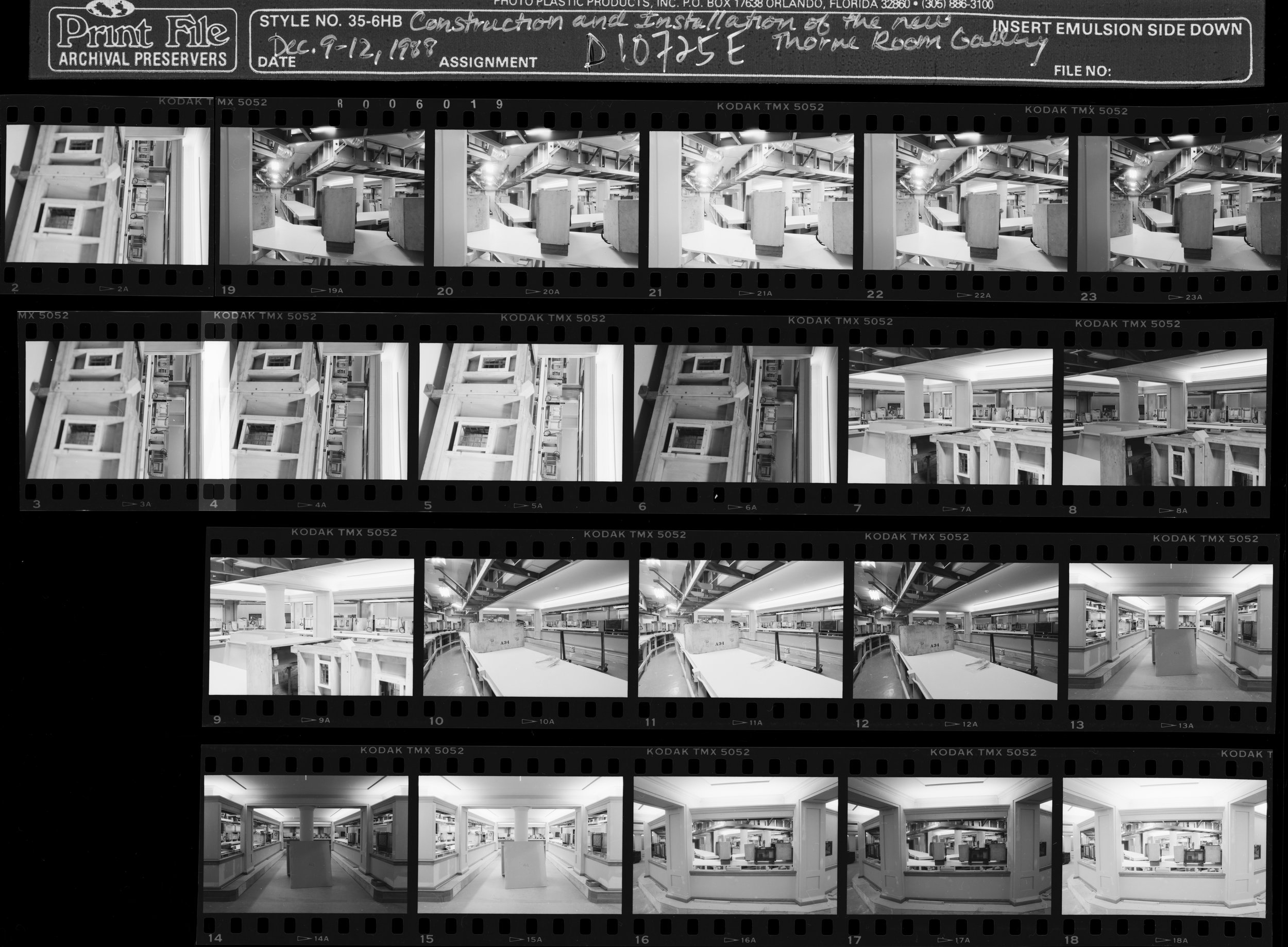

One such more general request came from the collection manager, conservation technician, and researcher of the Thorne Miniature Rooms at the museum. She emailed stating that looking for “all gallery and installation views” of the miniature rooms from their first installation to today. There was thus no defined right or wrong “answer,” and nearly any image could be useful. At first, I jumped in and attempted to locate as many images as I could alone. I performed a basic keyword search in our database, digitized several dozen contact sheets, and asked if I could be of further assistance. Only at this point did I start to understand how necessary ongoing conversation and an iterative approach to research is for more general requests like this one. This experience also taught me the value of following a more traditional reference process of query abstraction, query resolution, and query refinement (Pugh, 2008).

There were some gaps in the digitized contact sheets that I’d provided, and this staff member inquired if I could search again. We ended up meeting face-to-face, and she explained more fully what these images were for (to inform future interpretation of the miniature rooms, including wall labels and the installation of the rooms), and specific types of images that would be especially helpful (visitors looking at the rooms, position of lights in and around the rooms, views above and behind the walls and ceiling where the rooms have been installed). This interaction helped provide greater context in the form of her individual needs: the research purpose, intended use, and her previous experience and preparation (Pugh, 2008). This conversation served to more fully develop the query abstraction initially posed in her first email communication.

Given the limitations of our information retrieval systems, it is challenging to formulate the general topic in the form of a textual query. However, when we pooled our knowledge, we were able to find more relevant images. I ended up teaching this staff member how to use our information systems, and we worked together to formulate new queries, use different search terms, search in different fields, and generally try different methods to find images. Our process evolved and changed organically as we gained new information, much as Pugh (2008) describes Bates’s theory of berrypicking. This staff member was able to bring to the table expertise about the topic, and I was able to leverage knowledge about our systems and organization of knowledge. Through this query resolution, I helped steer her to relevant images while she provided additional points of access.

It is unlikely that this research will ever be “finished,” given the complexity of her request and the challenges of our information systems. Our query refinement may therefore be ongoing. It was rewarding teaming up to tackle this investigation, and it has informed how I facilitate other research queries.

References:

Pugh, M. (2008). Providing reference services for archives & manuscripts. Chicago, Illinois: The Society of American Archivists.