The College Art Association (CAA) held its annual conference in Chicago this year, and I was one of the fortunate staff who was able to attend from my museum. While many of the sessions were geared more towards those working in academia - especially college professors in arts and art history - I went to a number of sessions that dealt with photography, archives, and technology.

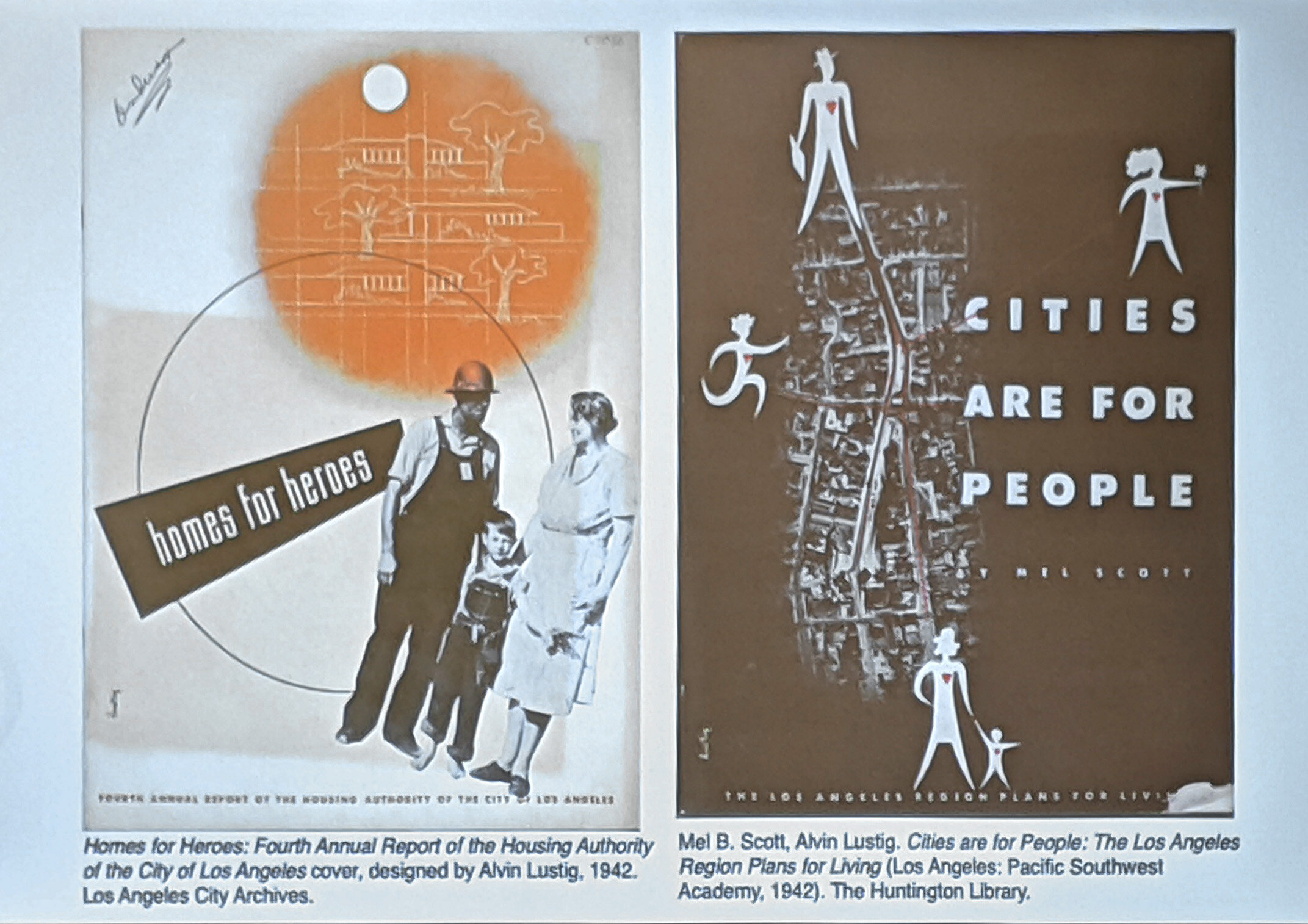

The role of photography in Los Angeles’ redevelopment

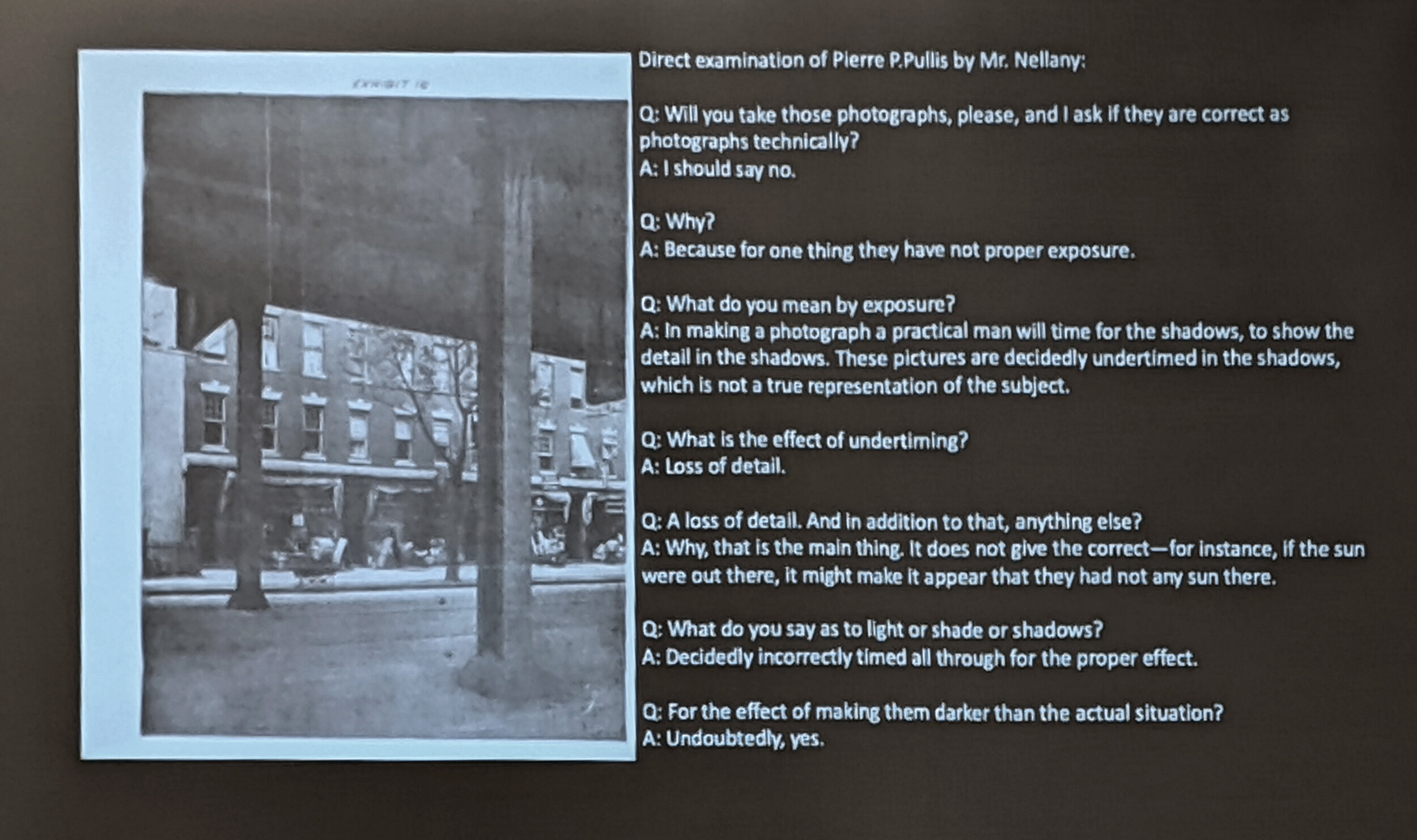

The first such session was entitled ‘Documenting Community Change,’ which addressed tension between renewal and preservation through a photographic lens. There were four panelists who presented - Documenting Urban Change as a Civil Wrong: A Case of Photographic Evidence in the Construction of the New York City Subway; Framing the Formless: Photography’s Urban Renewal in 1940s Los Angeles; A Pioneering Experiment: Documenting Urban Renewal in Hyde Park, Chicago; and The Bottom: The Interstate and Highways Defense Act & Segregation in Baton Rouge. The first presentation provided a wonderful early case study of how photography can be used in the court of law. The transcripts of the court proceedings underscored how photography may be conceived as evidence, as facts, and how subjectivity and creativity may obscure this objectivity. This feels like a challenge we still face today in how we conceive of lens-based images. The second and third presentations looked at cases where photography was an integral - and once again biased - way in which groups (a government branch or a university, in these cases) make their case for sweeping change. In both cases, photography was a tool used to “document” urban blight, and in Los Angeles, photo composites and graphic design then functioned as a stand-in to show what could replace this blight. The final presentation looked at a contemporary example of documenting shifting landscapes. This project featured community participation and demonstrated the power of lens-based media when it isn’t being used to capitalize off its subjects. I walked away from this session thinking a lot about photography, the photographic archive, and how viewers and researchers create meaning from images.

Transcript of court proceedings featuring discussion of the limitations of photography as evidence

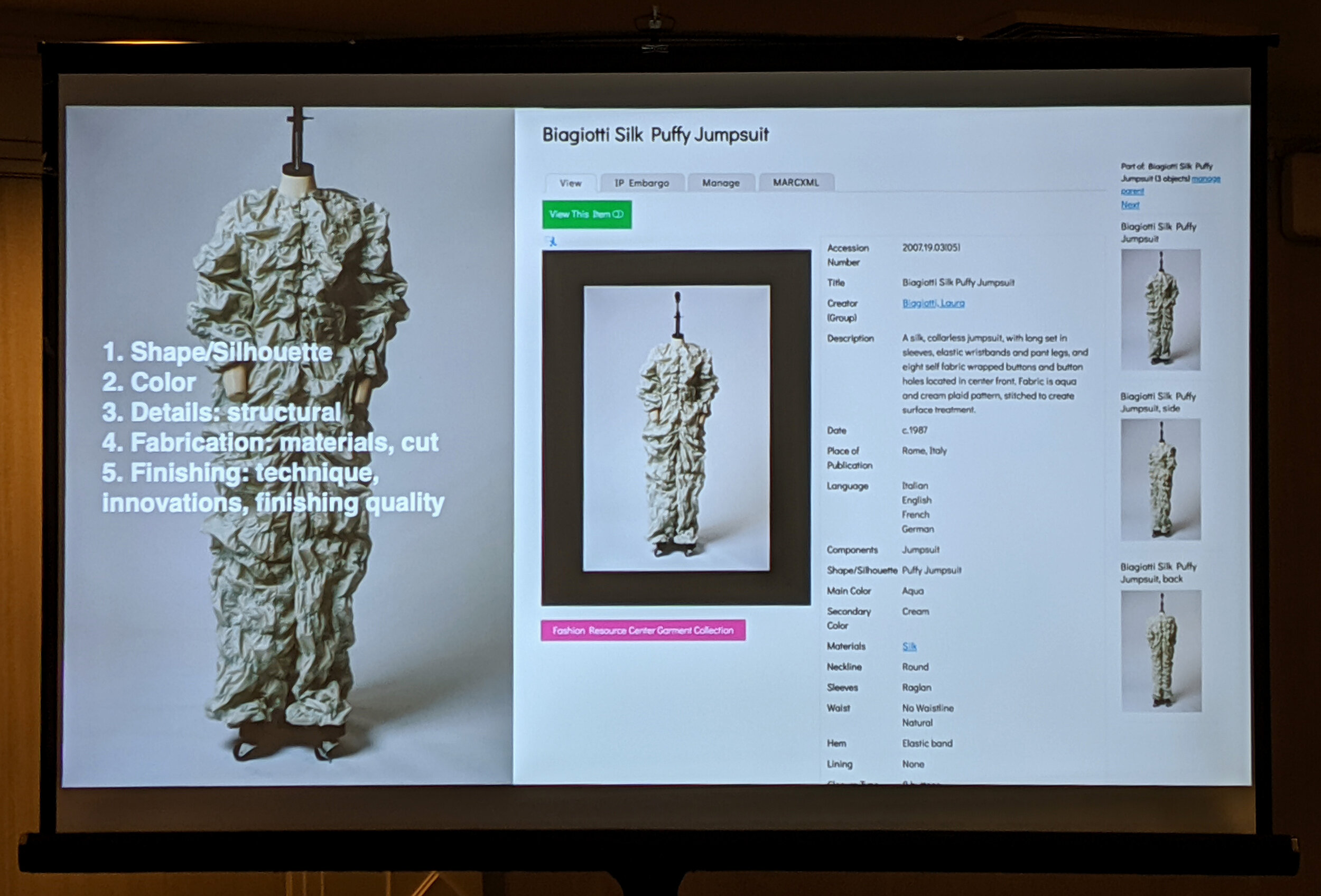

I also attended a session organized by the Visual Resources Association (VRA) - ‘Hands-on to Eyes-on: From Material Collections to Digital Exhibitions.’ Each of the presenters discussed the ways in which their institutions have leveraged special collections in classrooms at their colleges or universities. At Minneapolis College of Art and Design, for example, there is an object library of raw materials, replicas, original historic materials, tools, and pigments that art history professors can integrate into lectures. This allows students to more fully understand artwork as objects - materiality, process, creation - in conjunction with intellectual and aesthetic aspects of artwork. The School of the Art Institute of Chicago features a related teaching collection in the form of a textiles resource center - with 400 objects and 2,000 supporting books - and fashion collection - with 1,400 garments and accessories, and supporting videos and books. While these materials are fairly accessible to students, and staff managing these collections are actively digitizing and creating robust metadata to increase access. The last presentation brought in staff and faculty from the University of Chicago to discuss how the university has leveraged its art museum, the Smart Museum of Art, to incorporate hands-on curatorial training for students. Over the course of two quarter-long classes, university students had the chance to design and install an exhibit around a topic of the group’s choice, work that included: proposing theme ideas, combing the Smart Museum of Art’s collection for pieces to include, and generating interpretive text. The students functioned as a curatorial cohort and worked directly with museum staff on all aspects of the exhibit. It was fascinating to hear about the collaboration - the ways in which the museum benefited from the students’ insights, especially as it related to how objects were categorized in their catalog, and the ways in which the students were exposed to a range of work in the field. It is exciting to think about all the potential in archive, library, and museum collections, and how these materials can be used in educational contexts.

Special fashion and textiles collections at SAIC

Two sessions I attended towards the end of the conference dove into the role of technology in digitized and digital collections. In ‘Beyond the Algorithm: Art Historians, Librarians, and Archivists in Collaboration on Digital Humanities Initiatives,’ presenters discussed the ways in which their institutions are evolving with ever-changing tools and user expectations. They discussed IIIF, machine learning, collaborative projects, and database technologies. Conversations around metadata really resonated with me, especially the challenges of classification, geodata, and how we document gaps in our knowledge. It is encouraging to think about how linked open data may help to some of this end, as ownership and contribution of knowledge can be collectivized. The last session I attended, ‘Defining Open Access,’ evaluated if and how institutions should make available online their digitized and digital collections. There were compelling arguments from a variety of perspectives, and it was helpful to get a better grasp on some of the challenges: the manpower required to do this work; copyright, privacy, and traditional knowledge concerns; inconsistent rights statements in image records; understanding that open access may result in images or data being used in ways institutions do not always like. I am an advocate for making as much information - whether it be in the form of images, text, or time-based media - available to our users, and these presentations gave me a more nuanced understanding of when this may not be possible.

The conference also included optional field trips, and I am so happy that I decided to make the trek to the Harold Washington Library Center, the main branch of the Chicago Public Library, in order to tour their special collections. Archivist Michelle McCoy provided us with background information about the library and its special collections unit; the creator communities represented in the collections; and the prints, books, and objects she pulled to show us. I had no idea that the library had materials like sculptures, paintings, and miniature models in its holdings, and it’s so heartening to know that anyone can come in to view these materials.

The research room for the special collections at the Harold Washington Library Center

I decided to attend the conference fairly spur of the moment, and I walked away having learned so much. I feel fortunate to live in a city which is often host to larger conferences like these, and I hope to attend more like this one in the future.